by John Schlenck

Proponents of the play (Lila) theory of the universe are sometimes accused of not taking evil and suffering seriously enough. In The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna[1], a young visitor to Ramakrishna[2] protests, “But this play of God is our death.” The Master replies, “Please tell me who you are. God alone has become all this—maya, the universe, living beings…”

According to Vedanta we are the Self, the Absolute Being that is the essence of everyone and everything. Our real nature is pure Consciousness and Bliss. We may accept this intellectually, but until we experience it directly, we have to deal with evil, pain and suffering. Does the Lila theory trivialize evil? Does seeing evil as part of a grand cosmic drama trivialize it? Or does it make sense of it by putting it in a wider context?

What does the Lila theory say? That the universe is a free, spontaneous manifestation of divine bliss. To say that God has a purpose in creating the universe implies that God lacks something. If God lacked something, It would not be God. The universe is created without constraint or need, like the spontaneous play of a child. The illumined soul realizes this, seeing the divine presence in all things. “’He is the Great Poet, the Ancient Poet; the whole universe is His poem, coming in verses and rhymes and rhythms, written in infinite bliss.’”[3]

But what about the suffering we experience? What about the evil we perpetrate? According to the Lila theory, and to Vedanta in general, they are due to our limited, incorrect awareness. All that we do, even the worst that we do, is an attempt to uncover our intrinsic freedom and bliss. We seek wealth, pleasure and power, thinking they will make us happy, only to find that the satisfaction they give is short-lived. We lie, steal, cheat and manipulate, thinking that will get us what we want, but instead find that we are caught in a web of fear and loneliness. When we learn to see correctly, we will realize that God is behind and within everything, and we will be beyond any motivation to do evil. The attempt to regain that lost vision is at the root of all our activities. Like the lower bird in the Upanishadic parable,[4] we eat the sweet fruits of the tree until we find they don’t satisfy us. Then we look up and see the upper bird, calm, majestic and serene; we draw toward it and at last find we are one with it: it is our true Self.

Is the Lila hypothesis deterministic? Does it imply that we have no control over our lives? Seeing the universe as God’s play need not mean that we have no control over our part in the drama. We don’t have to see the play as pre-composed, permitting no editing. In fact, that would be contrary to the idea of God’s free play. Instead, we can see our lives as part of a divine game. God likes to see us play the game and so puts obstacles in our way. We gain strength by struggling to overcome these obstacles. The frustration and suffering we experience prod us to try to go beyond our present limitations.

Ultimately, all attempts to explain the existence of evil, in fact all attempts to explain how the universe is created, are conceptions of the human mind, and so are not absolute truth. According to Vedanta, as long as we are within maya—the relative world—we can’t know how or why it exists. And when we transcend maya the question no longer arises.

As long as we have not realized ultimate reality, we are faced with deciding how to live our lives. And so we may fairly ask, what effect do our ideas about the universe have on how we live? Do they stimulate us to engage in the spiritual quest, or do they depress and paralyze us? If we don’t like the Lila hypothesis, what other options do we have?

Let us consider several alternative explanations of evil.

Radical dualism: The world, and our life, is a battleground between cosmic good and cosmic evil. This philosophy is found in the Zurvanist branch of Zoroastrianism. A variant is also found in Gnostic Christianity, where spirit is good and matter is evil. There is a superficial similarity with the dualism of the Samkhya philosophy of Hinduism, except that in Samkhya, soul (purusha) and nature (prakriti), while separate, work in tandem. Prakriti is not thought of as evil; in fact, it nudges us toward freedom.

Original sin: Human beings are prone to evil because we are descendants of Adam, the first man, and we have inherited his disobedience of God. Our propensity for evil can only be overcome by the grace of God. We do evil when we allow ourselves to be tempted by the Devil or by our lower nature.

The tragic view: There is no meaning in the universe. Life is an accident. Moral good and evil are finally irrelevant. Good is whatever helps the individual or the species to flourish. We can heroically fight, but finally death conquers all. Like Sisyphus, we repeatedly roll an immense boulder up a hill, only to watch it roll back down.

Islam: We do evil when we act against God’s will; we do good when we submit to God’s will. If we are rebellious, we must wage a jihad to conquer ourselves.

Bhagavad-Gita: We do evil when we lack self-control and yield to rage and lust. [3:37-41] Pain, evil, and suffering can be overcome by knowledge and realization of the divine Self. Our duty is to fight the battle of life.

Buddhism: Suffering is basic to all life. Evil is something we create, and something we can overcome by our own efforts to purify ourselves. Why it exists is beside the point. We don’t need to know why and how the house caught fire; we need to get out of it. And there is a way out.

God is behind both good and evil. This idea is occasionally found:

- In the Hebrew Bible, as in Isaiah 45:6-7: “I am the Lord, and there is none else. I form the light, and create darkness: I make peace, and create evil: I the Lord do all these things.”

- In the Chandi, where the Divine Mother is both the great Devi (Goddess) as well as the great Asuri (Demon), [1:77] and in one instance is saluted as She who dwells in all beings in the form of error. [5:74-76]

- In the Gita, Chapter 11:32-33:

I am come as Time, waster of the peoples,

Ready for that hour that ripens to their ruin.

All these hosts must die; strike, stay your hand—no matter…

By me these men are slain already.

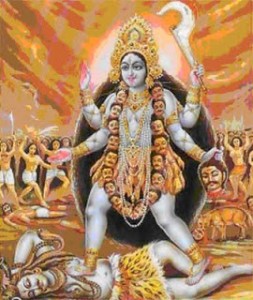

- In the image of Kali, whose right hands dispense boons and fearlessness while Her left hands carry a sword and a severed head.

This outlook is not for the faint-hearted, or for those who want to worship an all-good God.

Rather than viewing these different viewpoints as metaphysical abstractions, let us consider them as starting points for spiritual life, as images that can inspire and support our spiritual journey. Which one motivates us most effectively to undertake the journey? Each of us has to find her or his own answer.

Whatever path we choose, we have to move forward from where we are: Evil, pain and suffering exist. They are intrinsic to the human condition, the inevitable result of our sense of separateness. How do we deal with this situation?

If we see the underlying purpose and value of religion as spiritual transformation—evolving a God out of the animal man, as Vivekananda put it— different conceptions of God, human beings, and the universe can be seen as launching pads for different kinds of spiritual practice. These differing viewpoints should be evaluated according to how they motivate us. They can be seen as masks covering the face of Reality, and spiritual life as our effort to get behind the mask.

Except for the tragic view, all these views offer the possibility of transcending evil and suffering, whether by God’s grace or by our own efforts, or by a combination of the two. Let us consider how the Lila conception can motivate us.

Seeing evil as part of a divine drama, with faith that it can be overcome and is not absolute, can remove the burden of despondency and hopelessness about the human condition. We have the potential to play and win the game of life, the jihad for self-conquest. We can develop the skills needed to play the game. In Vivekananda’s words, “Thank God for giving you this world as a moral gymnasium to help your development … Be grateful to him who curses you, for he gives you a mirror to show what cursing is, also a chance to practice self-restraint; so bless him and be glad. Without exercise, power cannot come out; without the mirror, we cannot see ourselves.”[5] St. Paul wrote to the Corinthians, “Every athlete exercises self-control in all things. They do it to receive a perishable wreath, but we an imperishable.” [I- 9: 25.] To carry the analogy further, we may need help from a personal trainer. The avatars, seers, and prophets are like personal trainers. They can help us to gain the needed strength and skill to be good players.

If we are not athletically inclined, we can look on the universe as a divine dance. This concept is captured in the image of Shiva Nataraja, the cosmic dancer. When we contemplate the vastness, the intricate detail, the sublime beauty and terrifying power of the universe, we are filled with awe and reverence. We seek to know what is beneath the amazing surface, what is behind the shimmering mask. “The face of truth is hidden by thy golden orb, O Sun. That do thou remove, in order that I who am devoted to truth may behold its glory.” [Isha Upanishad, 15] Meditating on the image of Nataraj, we can study and practice how to participate in the cosmic dance, how to dance in sync with Shiva, and so overcome evil and suffering. As Ramakrishna said, “An expert dancer never takes a false step.”

There are different ways of viewing the divine play. Immersed in divine bliss, Ramakrishna experienced God as his blissful Mother and saw the universe as the overflowing expression of Kali’s blissful creativity. Vivekananda tended to emphasized the darker side of Kali’s play, as expressed through some of his poems:

For terror is thy name

And death is in thy breath,

And every shaking step destroys a world forever.

—from “Kali the Mother”

Shattered be little self, hope, name and fame;

Set up a pyre of them, and make thy heart a burning ground

And let Shyama dance there.

—from “And Let Shyama Dance There”

We learn more and faster through suffering than through ordinary happiness. The ancient Greek dramatist Aeschylus gave a powerful expression of this idea:

He who learns must suffer. And even in our sleep pain that cannot forget, falls drop by drop upon the heart, and in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom to us by the awful grace of God.

—Aeschylus, Agamemnon

Whether we emphasize the bright or the dark side, seeing and participating in God’s play willingly and intelligently can lead to spiritual freedom. Seeing the universe as a divine sport, a dance, a drama urging us toward spiritual freedom, challenges us to learn and play the game effectively. Taking part in a game, a ballet, a drama, developing the necessary skill and strength, can foster an elan [style and vigor, impetuous ardor] that carries us over obstacles and setbacks and enables us to persevere to the end. And the game itself, with its challenges to be met and the efforts we exert to master it, becomes enjoyable.

“This bitterly contested suit between the Mother and Her son—

What sport it is! says Ramprasad.

I shall not cease tormenting Thee till Thou Thyself

Shalt yield the fight and take me in Thine arms at last. [Gospel, p. 263]

Thinking of joy rather than suffering as basic to the universe, and finding joy in the process of spiritual life, can counteract depression and anxiety. We gain confidence and faith in our ability to play the game, we develop the strength and skill to persevere and cross hurdles, and the firm conviction that God-realization is our birthright.

Who could live, who could breathe, if that blissful Self dwelt not within the lotus of the heart? He it is that gives joy. [Taittiriya. Upanishad. 2.7.1]

[1] The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna (New York, Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center, 1952), 436

[2] He later became Swami Turiyananda.

[3] Swami Vivekananda, Complete Works, Vol. 2, Jnana-Yoga, “God in Everything.”

[4] Mundaka Upanishad, 3: 1-2; Svetasvatara Upanishad, 4: 6-7

[5] Complete Works, Vol. 7, “Inspired Talks.”

John Schlenck, a composer of music, was resident at the Vedanta Society of New York for many years, serving as Secretary, librarian and music director. Now living at the Vedanta Center of Atlanta, he is Coordinating Editor of American Vedantist and Secretary-Treasurer of Vedanta West Communications. Email: jschlenck@gmail.com

This is a very nice article, giving us a variety of options for facing evil and for self-transformation from various traditions and periods of culture. It incorporates not only the traditional Vedantic view of self-transformation to Brahman, but also several conceptual “levels” though which we can pass experientially on our way. A nice blend of so many features of Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Integral Vedanta

A very interesting article, thank you very much. I find I struggle with the ideas of determinism and free will. It seems that someone like Ramana Maharshi says all is determined. I presume this means in the physical realm. The article seems to imply we have free will in the “play”. I would appreciate if someone could point me in a direction that clarified these issues. That is I guess – is the free will only available in Consciousness or is it also available in Actions? ( according to Vedanta that is). My sense is the “world” of action is pretty much determined and its only our consciousness of this that is free. If anyone can assist me in these matters I would appreciate it very much. Thanks, Spike.

Well, my view is that all of these (samsaric) gods should pick on someone their own size and leave us be! :-)

As you quoted above, Ramakrishna answered his visitor’s protest about God’s play being our death with “Please tell me who you are. God alone has become all this—maya, the universe, living beings…”

The way I interpret this is that God isn’t ignoring our suffering (most notably, AWFUL AGONY); rather, in some sense, WE ARE God suffering.

From a standard theistic point of view, all the other explanations about building character through overcoming obstacles is perfectly consistent with such a God. When it comes to AWFUL AGONY (the holocaust, for example), a God at play while living beings endure this is callous. But, in a sense, IF WE are God suffering, there is no such callous personal superman God ignoring vast agony. The traditional trio of All Powerful, All-Loving, All-Knowing should be revised to exclude the “All-Powerful” component or to rethink the nature of God’s power. I largely construe the nature of God’s power to be his power to act in our souls (on the inside) to give rise to a sense of compassionate determination in us. There is no such supernatural being able to prevent tsunamis or immobilize bloodthirsty terrorists to prevent them from wreaking mass suffering and death. If all of us felt it important to nurture a connection with God-Consciousness, there would be less suffering (human-caused, anyway).