by Sister Gayatriprana

My interest in Integral Vedanta centers on transformation of consciousness. By that I am referring to the idea that consciousness can appear in a number of modes or states, each setting the “tone”, as it were, for the way we are aware of and perceive things. Furthermore, we can direct which way our consciousness develops these states through a process of self-transformation, or what in India is called yoga.

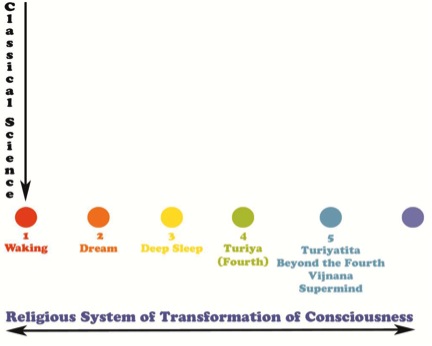

This notion, I feel, is the “operating system” behind spirituality, and the basic role of religion is as a kind of protector, nourisher, and sustainer of the quite long and often arduous process of transformation. In Diagram 1 I show states of consciousness arrayed horizontally, and an arrow indicating that the process of transformation can move either forward or backward in the Religious System of Transformation of Consciousness.

DIAGRAM 1: STATES OF CONSCIOUSNESS

I also show in the vertical dimension a one-way arrow pointing to the first of these states with the caption Classical Science. These two dimensions and captions indicate the difference between classical science and religion: Religion accepts many dimensions of consciousness, and classical science only one. This, I believe, is the source of the misunderstandings that have arisen between science and religion.

All of the major religions have touched on the idea of transformation of consciousness: John of the Cross’s Dark Nights of the Soul; Teresa’s seven-floored Interior Castle; and the ten Sephiroth of the Kabbalah. The Sufis have more than one system, as do the Buddhists and Hindus. But I think the earliest was in Vedanta. In the very earliest Upanishads (up to two to three thousand BCE) we read about the waking, dream, and deep sleep states, terms that although quite concrete, actually point to something more subtle, as is made clear in the Mandukya Upanishad, possibly from the pre-Buddhist period.

There we find a similar progression, but different terminology, where State #1 is described as focused on the external world, with which we identify ourselves fully. I indicate this state as a red circle. State #2, indicated as an orange circle, still cognizes the external world, but is also moving to the internal world, a situation where emotion, imagination and creativity come into play and our capacity to see meaning expands considerably. State #3 (a yellow circle) goes beyond inner and outer and sees the Atman, the Ground of Being, which transcends inner and outer and also supports them. Here we are able to discriminate between the Ground and the inner-outer dichotomy that preceded this state, and thereby gain a much greater depth of meaning to what we see. In the Mandukya there is also a fourth or turiya state (a green circle) in which there is no longer any inner or outer at all, and all that remains is the Atman, completely separate from any pair of opposites and able to be the impersonal witness of the progression from State 1 to State 3 and back again. The turiya state was what was specially celebrated by classical Vedanta, including Shankaracharya, and to become stabilized in it is indeed a rare and very significant event. But shortly after Shankara, talk about a fifth state began. It was called the turiyatita, or beyond the fourth (a blue circle), and was defined in Kashmir Shaivism as a state in which a person is permanently stabilized in the fourth but, unlike turiya itself, is able to fully involve him or herself in the activities of all of the states of consciousness. This, I believe, is what Vivekananda was referring to when he said that Ramakrishna was “alive to the depths of his being, yet on the outer plane, who was more active?” (Complete Works, Vol.5: Reawakening Hinduism on a National Basis, p.227.) This is a “people-friendly state”, unlike the Himalayan detachment of the turiya state. In Diagram 1 I also add a purple circle to indicate undifferentiated consciousness.

In the timeline of states of consciousness the fifth state is a newcomer, and I believe that Ramakrishna, Vivekananda, and Sarada were all well-developed contemporary expressions of it. Vivekananda transmitted it to Aurobindo in a series of mystic visions six years after Vivekananda’s physical death. For the rest of his life Aurobindo worked to understand it and study how it can be developed consciously and how it works in different realms of consciousness. His ideas about the most advanced states of consciousness caught the imagination of Integral thinkers like Ken Wilber, who, although they did not fully understand it, or even the classical progression of consciousness, took it seriously and gave it pride of place on the maps they created of structures of consciousness.

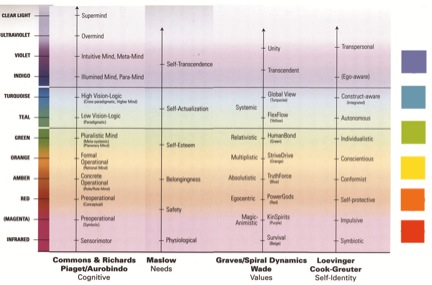

Although many of them were trained in science, these Westerners took states of consciousness seriously; but because they were embedded in the first state focus on external facts, it was so much easier for them to think about facts, history, concepts, evolutionary progressions, and so on rather than to become deeply stabilized in states of consciousness, they focused for the most part on what they called structures of consciousness: the different stages of cognitive development of children (Piaget, with Aurobindo added), of human maturation over a lifetime (Maslow); of social structures (Spiral Dynamics), of Self-identity (Loevinger and Cook-Greuter), for example. Each showed an “evolutionary” mode of development that Wilber conceived of in the vertical dimension as shown in Diagram 2.

DIAGRAM 2: STRUCTURES OF CONSCIOUSNESS

There he suggests the “height” to which any of these systems reached by the range of colors in the spectrum of light; red is the least evolved, and purple the most, fading off into white light at the top. We can see that the three purely Western systems penetrate up very high into the realms described by Aurobindo: Illumined Mind, Intuitive Mind, Overmind; but none of these Western researchers have documented Supermind. So Supermind is an ideal that interests the West, but is not yet accessible to it. In this diagram I have added for comparison the six colors I used in Diagram 1, located at similar points on the overall map, but in a square shape to differentiate structures from states.

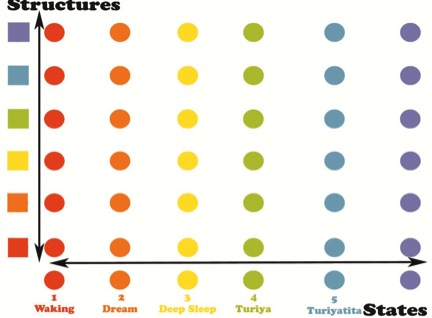

Having created quite a library of different structures, Wilber and others asked themselves, “Where do states fit into all of this?” Their big breakthrough occurred in the last decade, when they realized that states were not extensions of structures, but actually operated in a different dimension, as indicated in Diagram 3, where I follow the Western convention of indicating structures (colored squares) in the vertical dimension and states (in the usual colored circles) in the horizontal dimension. These form what Wilber and others call a lattice.

DIAGRAM 3: THE WESTERN LATTICE

This was primarily an intellectual construct, but it carried the important insight that if you were in any structure, you could explore it from within, as it were, by experiencing the five states. For example, the materialism of structure #1 could be “expanded” from within by going deeper and deeper into states of consciousness within its purview. This, I believe, is what Vivekananda talks about in his Karma Yoga. It also carried the message that if you had a fifth state experience but were fixed in a second structure, the way you would interpret the experience would be limited by second structure ideas and understanding—perhaps what Vivekananda was talking about when he mentioned that Muhammad had high realizations that had to be worked out on a much less evolved plane of understanding, thereby distorting the message considerably.

The West has noticed that the notion of structures of consciousness is a recent phenomenon, beginning probably with Baldwin in Vivekananda’s lifetime. Integral folks rather tend to plume themselves on the notion that the West trumped the East in this respect; and certainly adding the dimension of structures to states does explain a lot and add important dimensions to our understanding of consciousness. But in my own studies of the interchanges between Ramakrishna and Vivekananda I noticed that both of them had an array of five themes that they mentioned all the time and always together, and which I think is as much an evolutionary array of structures as anything the West has come up with.

Diagram 4 shows these themes colored according to our conventions. These structures, of course, are not physical, historical, psychological, or anything that can be measured. They are, actually, a range of solutions to the besetting contradictions between East and West, showing the same progression from the material (humanism) to the purely noetic (holism) as the structures touted in the West.

DIAGRAM 4: RAMAKRISHNA’S THEMES

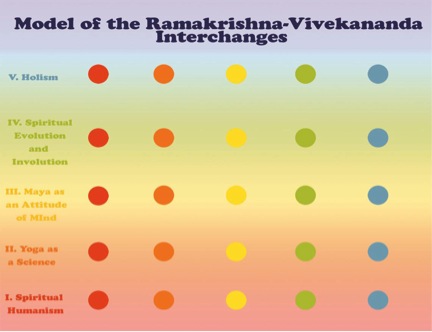

Furthermore, in practice they were presented, not as a series to be learned one by one through painstaking struggle (as the West imagines the progression along the structures), but as a spectrum to be studied and digested as a whole. Diagram 5 gives an idea of how Vivekananda worked this through as he was learning from Ramakrishna. Ramakrishna’s spectrum of structures is represented in a gradient including our five colors. As Vivekananda accessed State 1, he was expected to “irradiate” all of the structures on the map with that consciousness, a situation shown in the diagram as five red circles, each engaging one of the five structures. The same is true for all of the states, which are seen “engaging” with the array of structures.

This arrangement was arrived at from a detailed study of the interactions between Ramakrishna and Vivekananda at each “node” of these intersections. This is not a theoretical model like the lattice, but built up on actual, historical facts (including Vivekananda’s noetic transformations). In this sense it is a much more tightly knit and worked-out version of the Western lattice, which at the moment is largely theoretical, although there are researchers beginning to plot out what kinds of psychological phenomena occur at these nodes.

DIAGRAM 5:

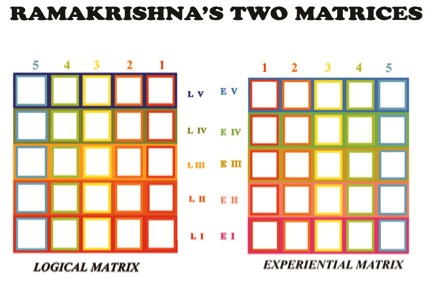

Our Vedantic model, (which I call a matrix to distinguish a configuration based on actual data, as opposed to the as yet theoretical model of the lattice) also provides another wrinkle that I will just mention here: Ramakrishna not only worked Vivekananda through five states of consciousness and five connected structures; he did it in two different ways, using two different kinds of language. That I show in Diagram 6 in two mirror-image matrices. The one on the left is what I call “logical”, i.e. rational, didactic, and consistent. The other was “experiential”, i.e. phenomenological, expressive, and coherent. You could call these two modes left and right brain, West and East, or any other pair of opposites that seem to fit the bill. The result is a very closely knit series of exchanges, each quite specific for its “location” on the map, fleshing out the implications of the Western lattice.

DIAGRAM 6:

I believe that if the discovery of the lattice in the West was an integral breakthrough, the Vedantic creation of fleshed-out matrices in two different dimensions is integral squared, at the very least.

I believe that if the discovery of the lattice in the West was an integral breakthrough, the Vedantic creation of fleshed-out matrices in two different dimensions is integral squared, at the very least.

SISTER GAYATRIPRANA is a writer on Vivekananda Vedanta with a background in the neurosciences. Formerly a monastic member of the Vedanta Society of Southern California, she retired to Santa Fe, New Mexico.

This is a brilliant, insightful, and most welcome corrective to the predominantly left brain approach of Wilber. I was surprised also to see someone else knew about the relatively obscure fact of Vivekananda’s transmittal of his vision to Aurobindo (when the latter was in jail, nonetheless – for being a suspected terrorist!!).

Thank you so much. I hope there’s more of your writing. i’m going off to look for it now!