by John Schlenck

Most revolutionaries are remembered for one particular revolution: George Washington for the American revolution against British imperial rule, Adam Smith for the creation of modern political economics, Lenin for the Communist revolution in Russia, Einstein for superseding Newton and creating modern physics, Haydn for creating modern musical structure.

But there are a few historical figures who effected multiple revolutions.  Leonardo da Vinci was not only the greatest painter of his time but also revolutionized the study of anatomy, the scientific observation of nature, and the mindset of systematic technological innovation.

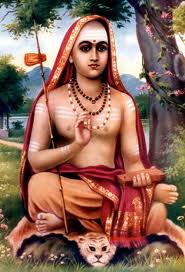

Leonardo da Vinci was not only the greatest painter of his time but also revolutionized the study of anatomy, the scientific observation of nature, and the mindset of systematic technological innovation.  Shankaracharya not only established the supremacy of Advaita Vedanta among Indian religious philosophies but also created the shape of medieval Hinduism, giving it a structure that could withstand nearly a thousand years of foreign domination.

Shankaracharya not only established the supremacy of Advaita Vedanta among Indian religious philosophies but also created the shape of medieval Hinduism, giving it a structure that could withstand nearly a thousand years of foreign domination.  Gandhi not only freed India from foreign domination, but did so in a revolutionary manner through the application of spiritual principles to politics on a mass scale, creating a method of protest applicable in any time and place.

Gandhi not only freed India from foreign domination, but did so in a revolutionary manner through the application of spiritual principles to politics on a mass scale, creating a method of protest applicable in any time and place.

Swami Vivekananda is one such multi-faceted revolutionary. He revolutionized Indian monasticism, did more than any other to forge India’s concept of itself as a single entity, gave India back its pride and confidence in its own culture, effected in the West a new spirit of religious toleration and respect, introduced yoga to the West, and, what is often not appreciated, made Hinduism independent of Indian culture. And he revolutionized Vedanta itself.

THE MONASTIC REVOLUTION

Based on a single utterance of his Master, Sri Ramakrishna,[1] Vivekananda created a new type of monasticism. Monks were not only to seek their own enlightenment through meditation and prayer, but to render hands-on service to the people—education, medical treatment, emergency relief from natural or manmade disaster.  Social service would be based on Vedantic principles. The recipients of service would be viewed as living forms of God, to be served and reverenced. Based on the model he established through the Ramakrishna Mission, virtually every new Hindu monastic organization since Vivekananda, from Bharat Sevashram Sangha to Mata Amritanandamayi Mission Trust, has undertaken social service. It is now normative. How revolutionary this was can be seen from the opposition and ridicule he and his early followers faced. But by sheer force of character and their living examples of love and unselfishness, they triumphed.

Social service would be based on Vedantic principles. The recipients of service would be viewed as living forms of God, to be served and reverenced. Based on the model he established through the Ramakrishna Mission, virtually every new Hindu monastic organization since Vivekananda, from Bharat Sevashram Sangha to Mata Amritanandamayi Mission Trust, has undertaken social service. It is now normative. How revolutionary this was can be seen from the opposition and ridicule he and his early followers faced. But by sheer force of character and their living examples of love and unselfishness, they triumphed.

THE INDIAN REVOLUTION

Though Vivekananda was not the first to see India as an integral whole, he probably did more than anyone else to forge this awareness. How did he do this? By restoring the people’s faith in themselves and their heritage. Whatever the long-term effect Vivekananda’s work had on the West itself, the respect for India that he gained in the West had a galvanizing effect on Indians, giving them confidence and pride in their own heritage. His call to awake and arise was heard. The revolutionary effect of this call was acknowledged by the British authorities. During the pre-Gandhi revolutionary movement, it was observed that, though Vivekananda’s writings did not contain any statements against British rule, nearly every detainee had a set of Vivekananda’s works in his prison cell. By the time Gandhi returned to India from South Africa, the idea of a unified India was well established, and Gandhi could build upon it to make it a political reality.

THE REVOLUTION IN INTERFAITH RESPECT

The World Parliament of Religions held in Chicago in 1893 was itself revolutionary. Just putting representatives of the major world religions side by side on the same platform implied equality and mutual respect.  This had never been done before. Vivekananda seized on these implications to present his and his Master’s vision that all religions are valid paths to the same goal. He gave full-throated voice and inspired eloquence to the implied message of the Parliament, and afterward he toured large sections of the United States spreading this message, as well as creating respect for Indian spirituality, to cities and towns across the country. A strong case can be made that by doing this he jump-started the interfaith movement in America. As with Vivekananda’s new monastic ideal in India, how revolutionary Vivekananda’s ideas were in America can be seen from the opposition he aroused, to the extent of attempts on his life. As with the acceptance of his monastic ideal in India, the success of this revolution of interfaith acceptance has become increasingly apparent, in spite of setbacks. Recent polls show that a majority of Americans now believe there is more than one path to spiritual truth. President Obama recently paid homage to this revolution in his address to the Indian Parliament, lauding “a visitor to my hometown of Chicago more than a century ago—the renowned Swami Vivekananda. He said that ‘holiness, purity and charity are not the exclusive possessions of any church in the world, and that every system has produced men and women of the most exalted character.’”

This had never been done before. Vivekananda seized on these implications to present his and his Master’s vision that all religions are valid paths to the same goal. He gave full-throated voice and inspired eloquence to the implied message of the Parliament, and afterward he toured large sections of the United States spreading this message, as well as creating respect for Indian spirituality, to cities and towns across the country. A strong case can be made that by doing this he jump-started the interfaith movement in America. As with Vivekananda’s new monastic ideal in India, how revolutionary Vivekananda’s ideas were in America can be seen from the opposition he aroused, to the extent of attempts on his life. As with the acceptance of his monastic ideal in India, the success of this revolution of interfaith acceptance has become increasingly apparent, in spite of setbacks. Recent polls show that a majority of Americans now believe there is more than one path to spiritual truth. President Obama recently paid homage to this revolution in his address to the Indian Parliament, lauding “a visitor to my hometown of Chicago more than a century ago—the renowned Swami Vivekananda. He said that ‘holiness, purity and charity are not the exclusive possessions of any church in the world, and that every system has produced men and women of the most exalted character.’”

THE YOGA REVOLUTION

Vivekananda’s introduction of yoga to the West can also be regarded as a revolution, though it was slow to catch fire until recent decades. Yoga, with its systematic practices to transform mind, body and consciousness, is now an integral part of American culture. The accompanying implication—that spiritual transformation does not require belief in a creed—is also increasingly accepted, even taken for granted.

HINDUISM’S INDEPENDENCE FROM INDIA

Another revolutionary achievement of Vivekananda is not so well recognized and appreciated: he made Hinduism independent of Indian culture. From ancient times, Hinduism, unlike Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam, had spread not as a transcultural idea, but only as part of the package of Indian culture. Vivekananda went a long way toward making the basic ideas of Hinduism (which he called Vedanta) culture-neutral. That he worked on this consciously can be seen from his statement in a letter to a disciple,

. . .to put the Hindu ideas into English and then make out of dry philosophy and intricate mythology and queer startling psychology, a religion which shall be easy, simple, popular, and at the same time meet the requirements of the highest minds— is a task only those can understand who have attempted it. The dry, abstract Advaita must become living— poetic— in everyday life; out of hopelessly intricate mythology must come concrete moral forms; and out of bewildering Yogi-ism must come the most scientific and practical psychology— and all this must be put in a form so that a child may grasp it. That is my life’s work. The Lord only knows how far I shall succeed.[2]

This may seem strange, given his deep love for India and her civilization. But there are statements he made showing that his vision transcended culture and nationality. He saw the human race as an undivided whole.

What is India or England or America to us? We are the servants of the God who by the ignorant is called Man.[3]

Whatever was best in the whole human heritage, whatever ennobled and uplifted human beings, was to be valued.

THE VEDANTIC REVOLUTION

The history of Vedanta, in broad outline, may be said to consist of three periods: ancient, original Vedanta of the Upanishads and the Bhagavad-Gita; medieval Vedanta of Shankara and other commentators; and modern Vedanta, especially from Swami Vivekananda onward. What distinguishes medieval Vedanta from both ancient and modern is its almost total concern with personal liberation, its vision of spiritual life as something unrelated to social life. Of course, it takes for granted that the spiritual seeker is born into a social context. Indeed, he must be born into just the right physical and social context, according to Shankara: a male, Brahmin body. But his business is to rise above even that exalted position, to isolate himself from all material and social fetters and realize his identity with the Godhead.

AGAINST THE MEDIEVAL VIEWPOINT

Swami Vivekananda unleashed a revolution against this medieval viewpoint. The initial inspiration for this revolution came from Sri Ramakrishna, who scolded Vivekananda for wanting to remain continually immersed in samadhi. The real goal, Ramakrishna chided the young Narendra, was to see Brahman in everything.

Ramakrishna also did not uphold Shankara’s sexism. His first guru was a woman; his first disciple was a woman; he worshipped his own wife as the Divine Mother. One of his women disciples, Gauri-Ma, was a monastic. He got around the traditional bias against women becoming nuns by saying, “If a woman embraces sannyasa, she is certainly not a woman; she is really a man.”[4] This may still sound sexist to our ears, but we have to appreciate this forward step in the context of its time.[5] Ramakrishna took a further step forward by commissioning Gauri-Ma to do social service for the uplift of women. When she suggested “training a few girls” in the quiet isolation of the Himalayas, he insisted that she work in Calcutta itself.

There were other factors behind Vivekananda’s Vedantic revolution. His large heart was powerfully moved by the human suffering he saw during his years as a wandering monk. As recorded in The Eternal Companion,[6] Vivekananda’s brother-disciple Swami Brahmananda said to his disciples, “While Swami Turiyananda and I were living on Mt. Abu, we received a letter from Swami Vivekananda just before his departure for America. He wrote, ‘To devote your life to the good of all and to the happiness of all is religion. Whatever you do for your own sake is not religion.’ How wonderful is this truth! His words are engraved on my heart.” Vivekananda saw that each person must grow spiritually from where he or she was, and that preaching metaphysics to starving people was madness. In addition, his study of the ancient scriptures and his own spiritual experiences led him to reject the medieval vision in which only a privileged few could aspire to spiritual freedom, giving up all social concerns, while the majority were to practice social and ethical virtues and devotion to the personal God. Vivekananda, without caring for orthodox criticism, preached Vedantic realization to all, high and low, men and women, Hindus and non-Hindus. He founded a monastic organization whose motto was “for one’s own salvation and for the good of the world” (emphasis added).

VEDANTIC TRUTH FOR ALL

Vivekananda’s revolution in many ways carries Vedanta back full circle to its ancient roots. The great Upanishadic spiritual adventure was undertaken by all sections of society, men, women and children, brahmins and non-brahmins, kings, merchants, priests, warriors, farmers and housewives. Realization does not depend upon monastic isolation. In the Mahabharata, a renunciate learns first from a housewife and then from a butcher. In an Upanishad, the illegitimate child of a maidservant is accepted as a disciple and afterward becomes a knower of Brahman.

Vivekananda, coming to the West, preached Vedanta without reservation, convinced that Westerners could realize Vedantic truth. He also expanded the traditional purview of Vedanta to include all paths. The aspirant could realize Brahman through devotion, through concentration, through spiritual discrimination, and through unselfish work. Not since the Bhagavad-Gita had such a synthesis been preached.

KARMA-YOGA ACHIEVES EQUALITY

Vivekananda’s special contribution was his emphasis on karma-yoga. It has well been said that each of the other paths had their commentators: Patanjali for yoga, Shankara for jnana, Narada for bhakti. But it was left for Vivekananda to codify karma-yoga and to give it a central place in the organization he started, the Ramakrishna Mission.[7] Shankara regarded karma-yoga as only a preliminary stage in spiritual life, as a preparation for jnana-yoga. In addition, he looked upon karma-yoga as mostly the performance of rituals, rather than as unselfish service to others. Vivekananda changed all that. One could realize Brahman purely through unselfish work, as had the housewife and the butcher in the Mahabharata story. In actual practice, most of us follow a combination of two or more yogas. But Vivekananda put karma-yoga on an equal footing with the other paths.

This new emphasis on karma-yoga is especially important for the modern world with its emphasis on doing rather than thinking. It is also especially helpful to the Western spiritual seeker, who rarely grows up with any training in contemplative life. Is childhood training important? Without digressing, it is fair to say that all psychologists agree that a child’s earliest years are exceedingly important. But does this debar Westerners from aspiring to God-realization? Not at all. A few are naturally contemplative. Others can follow other paths. Vivekananda has opened the gates to all by teaching all paths. In reality most spiritual aspirants, even in India, do not follow one yoga exclusively.

FULL HUMAN DEVELOPMENT

Vivekananda’s ideal for the modern world was the integration of all paths in all lives. Only the proportion would vary according to individual temperament and capacity. All should develop their power of concentration, all should purify and focus their emotional life, all should develop their intellect and power of discrimination, and all should work with dedication and unselfishness. And in fact there are no watertight compartments between our active, emotional and intellectual selves. Emotional development without discrimination and clarity of thinking may lead to fanaticism or sentimentality. Intellectual sharpness and discrimination without emotional growth leads to dryness and lack of feeling for others. Concentration requires a focus, internal or external, and that focus must inspire our emotional and intellectual commitment. And selfless work, to be sustained, requires introspection as well as emotional and intellectual purification.

Vivekananda opened a new vista of all-round human development, both for the individual and for society. In these matters, there is no East or West. But the particular way these ideals are put into practice will depend on circumstances. If we are committed to the spread of these ideals, let us note that in our modern world, unselfish service is respected by all people, religious or secular. Thus if dedicated service is undertaken by Vedantists wherever they are, it will help them gain general respect and acceptance in their respective countries, and also will make Vedanta more widely known. As Vivekananda himself said, “However much their systems of philosophy and religion may differ, all mankind stand in reverence and awe before the man who is ready to sacrifice himself for others. Here, it is not at all any question of creed, or doctrine—even men who are very much opposed to all religious ideas, when they see one of these acts of complete self-sacrifice, feel that they must revere it.”[8]

Although the general emphasis of Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Vedanta has been on spiritual teaching in the West and social service in India and adjacent countries, Vedantists inside and outside the Ramakrishna Order are now undertaking both social service and teaching in different parts of the world. Devotees and Centers in the United States are becoming engaged in service to disadvantaged Americans—food to the homeless, spiritual literature to prisoners, cassette recordings to the blind—and to people in India, through ASTI (American Service to India.), which supports medical and other service work there. In South Africa, Ramakrishna-Vivekananda devotees are serving disadvantaged members of the black community as well as the Indian community there.

When Swami Ranganathananda, former President of the Ramakrishna Order, was asked why the Vivekananda Rock Memorial project (building a temple on Vivekananda Rock at Kanyakumari and the service work that followed) was not under the management of the Order, he answered, “Swami Vivekananda is nobody’s property.” Indeed, Vivekananda and the modern form of Vedanta he pioneered belong to the whole world. It is for men and women everywhere to take up these ideals, build their lives on them, and become a blessing to themselves and to society. • • •

[1] “No, no, it is not compassion for others … it must be service to all creatures, recognizing that all creatures are God (jive Shiva).” Dhar, Sailendranath, A Comprehensive Biography of Swami Vivekananda (Madras: Vivekananda Prakashan Kendra, 1975), Vol. 1, p. 148.

[2] Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda, Vol. 5 (Calcutta: Advaita Ashrama, 1979), 104-105.

[3] Complete Works, Vol. 8 (1977), 349.

[4] The Gospel of the Holy Mother (Madras: Sri Ramakrishna Math, 1984), p. 159.

[5] It should be noted that in recent decades orders founded by Shankara himself have admitted women, non-brahmins and foreigners.

[6] Swami Prabhavananda: The Eternal Companion: Brahmananda, Records of his teaching with a biography (Hollywood: Vedanta Press, 1947), p. 208.

[7] We are indebted to Swami Sarvagatananda for this analysis.

[8] Complete Works, 1: 86.

JOHN SCHLENCK is a resident member and Secretary of the Vedanta Society of New York and a composer of music. He is also Secretary-Treasurer of Vedanta West Communications and Coordinating Editor of American Vedantist. Email: jschlenck@gmail.com

Thank you very much Mr John for representing the Swami Vivekananda’s multidimentional personality in a few words. A very authetic and authoritative article. Nearly all the aspects of his teaching has been covered in very few and nice words. Teachings of the Vivekananda are universal. His audience are people of all the nations and all the races on the earth. He himself had declared that ” What is India or England or America to us? We are the servants of the God who by the ignorant is called Man”. What he preached is not meant for India and America only. Both the nations , at that time represented two aspects of the reality and new synthesis and equilibrium was needed. Real import of his teaching are yet to be realized. Journey started from Chicago has not reached to it’s destination. It is very slow but marching forward. Once Swamji had himself said that what he has time in short span of time can be assessed by another Vivekanda only!

Thank you for your proper realization

oh Hinduism as a package of culture.

Swami Vivekananda distinguished between theoretical reference of Vedanta and practice and paraxis of religion. And synthesized the idea of practical Vedanta.

Love-respect and pronam.