As I move past the half-century mark, it begins to dawn on me that perhaps the passages of my life are not quite as disparate or accidental as I thought they were. With or without my active participation, the needle on my compass had been set with a bias toward spiritual ideas. Perhaps that sums up divine grace. We are all on the road toward Godhead, but the signposts in my case were frequent, probably because it took some prodding to register the message. Beginning with spiritual grandparents and parents who took my (often unenthusiastic) self into the presence of realized gurus and saints, God knocked on my door pretty insistently—nay, I would say hammered on it, pulled my inward spirit back and back, gave me just enough trials to weaken my material bonds, and enough elevating encounters to inspire my inward yearning. I have no choice but to be conscious of spiritual links, because God made it impossible to do anything else by showering abundant evidence of divine presence. Occasionally, I will drift into the idle delusion that my operating system has moved away from naiver beginnings into a more complex and discrete secular world. That’s usually when a subtle cosmic nudge reveals the recurring connections that underpin my steps through the world. Sometimes these revelations materialize after decades, no doubt because that is when I am ready to value the moment.

As I move past the half-century mark, it begins to dawn on me that perhaps the passages of my life are not quite as disparate or accidental as I thought they were. With or without my active participation, the needle on my compass had been set with a bias toward spiritual ideas. Perhaps that sums up divine grace. We are all on the road toward Godhead, but the signposts in my case were frequent, probably because it took some prodding to register the message. Beginning with spiritual grandparents and parents who took my (often unenthusiastic) self into the presence of realized gurus and saints, God knocked on my door pretty insistently—nay, I would say hammered on it, pulled my inward spirit back and back, gave me just enough trials to weaken my material bonds, and enough elevating encounters to inspire my inward yearning. I have no choice but to be conscious of spiritual links, because God made it impossible to do anything else by showering abundant evidence of divine presence. Occasionally, I will drift into the idle delusion that my operating system has moved away from naiver beginnings into a more complex and discrete secular world. That’s usually when a subtle cosmic nudge reveals the recurring connections that underpin my steps through the world. Sometimes these revelations materialize after decades, no doubt because that is when I am ready to value the moment.

Thus, though I was born in Calcutta, and often visited Dakshineswar, Kalighat and Belur Math, I’m forced to confess that all I felt during these outings was annoyance with the crowds, boredom with the rituals, or resentment at squelching barefoot through monsoon mud in order to pray to a Kali that no one asked me if I wanted to go see (anyway, Krishna was my favorite then). Since my preference wasn’t consulted, I acquiesced while my parents conducted what seemed like every visitor who ever stayed with us to Belur and Dakshineswar. Even though I began to enjoy philosophy, read Vedanta and attend lectures as I grew older, I nonetheless, inexplicably, overlooked the spiritual giants in my backyard. It was not through arrogance, but rather the commonplace of the familiar. I thought I knew all about them simply by virtue of merely being surrounded with their names, words and images at every turn.

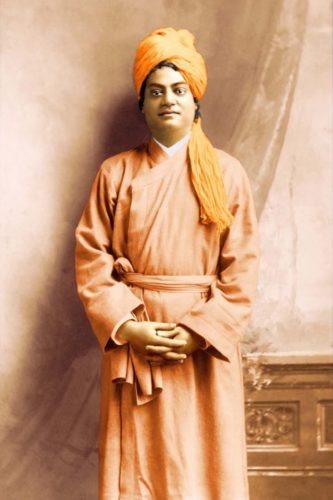

I lived in Calcutta until I left in 1985 to attend Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts. I was a transfer student from Presidency College, Calcutta—a college with a list of distinguished alumni long enough to make one’s head spin. Of course, a far more famous Presidency alumnus from a century before my time was Swami Vivekananda, then called Narendranath Dutta. The spiritual colossus had touched that institution too, though I gave little thought to it at the time.

But America was a planet removed from all that, right? Or so my younger self thought as I plunged into my college years at Smith, now able to study art and literature, and visit places I had dreamed of seeing—smart Western cities with grand architecture, entertainment, facilities, and exciting fresh ideas. I graduated in 1988, worked, traveled, married an American, and became slightly more patient (helped by the afore-mentioned hard experience). I also met my own guru, and the spiritual flame continued to grow and evolve. God takes a while to let the metal heat up for the hammer.

Fast forward to November 2017 and I’m in India to visit my folks, who had long since moved away south. In an unusually synchronized moment, it seemed as though we were all seized with the desire to re-visit Calcutta. My parents, brother, and I travelled there together after 30 years, and it was extraordinarily poignant. On the last day we visited Belur Math at my mother’s request, indulging her with good grace, or so I thought. But I guess I had finally grown up enough to be a bit more humble and open. This time, in the serenely beautiful setting on the bank of the Ganges, I grasped the phenomenon that was Swami Vivekananda. I cannot say why, but as I walked under Swamiji’s tree, viewed his room, and circumambulated his samadhi looking out over the river, I began, at last, to perceive what had been there all along. It was stunning to realize that over a century ago, a singular young monk had left India to bring Vedanta to the West, and, in doing so, left such a tremendous body of work. No conventional entourage, funding, network, or organization had sustained his quest. It seemed incredible that he accomplished all that he did before he was forty. At the excellent bookshop, where I belatedly realized that I had never voluntarily read a book about Swamiji, I bought three different biographies, one for each of us, with the idea that we could exchange them down the road to get a broader picture.

A month or so later, back home in the US, I got a message from my parents with a picture of a page in their copy of his biography. It referred to Vivekananda’s stay on Smith campus in Northampton, where he gave a speech at both City Hall, and, following vespers services, to Smith students. He stayed on campus from April 13 to 16, 1894, during the tour following his meteoric appearance at the Parliament of Religions. To say that I was amazed to learn of this hidden connection is an understatement. Here I thought I had traveled far from my roots in Calcutta, and Swamiji had been at my American college a century ago, attempting to bridge the East-West divide that many Asian foreign students are familiar with. It was also somewhat mortifying to have been unaware of this for 30+ years! Why didn’t I know about it?

I dug around to find out, and part of the answer lay in the fact that the college itself seemed to have forgotten its brilliant visitor. There was only a brief mention in a Smith College Monthly in May, 1894; “On Sunday, April 15, Swami Vivekananda, the Hindoo monk whose scholarly exposition of Brahmanism caused such favorable comment at the Congress of Religions, spoke at Vespers.” This was followed by two sentences summing up the talk, and no transcript was available. It was rather like finding out that Dr. Martin Luther King or George Washington had given a speech at Smith, but no one had made a note of it or documented their sojourn on campus.

Casting around some more revealed a couple of great little sources, one being a pictorial account of Vivekananda’s travels,1 which referenced the recollections of Martha Brown Fincke, a Smith freshman in 1894. She recounts her experience 42 years later, while visiting Belur Math in November 1935.2 She recalled how, as an immature freshman, and raised as an observant Protestant, she was intrigued and excited to hear that a Hindu monk would visit Smith and stay at her college house.

“On the Bulletin for November was the name of Swami Vivekananda who was to give two evening lectures. That he was a Hindu monk we knew, nothing more; for the fame he had won in the recent Parliament of Religions had not reached our ears. Then an exciting piece of news leaked out; he was to live at our house, to eat with us. and we could ask him questions about India. Our hostess’ breadth of tolerance may be seen in receiving into her house a man with dark skin, whom the hotel had doubtless refused to admit. As late as 1912 the great poet Tagore with his companion wandered through the streets of New York looking in vain for shelter.

The day came, the little guest-room was ready, and a stately presence entered our home. The Swami’s dress was a black Prince Albert coat, dark trousers, and yellow turban wound in intricate folds about a finely shaped head. But the face with its inscrutable expression, the eyes so full of flashing light, and the whole emanation of power, are beyond description. We were awed and silent. Our hostess, however, was not one to be awed, and she led an animated conversation. I sat next to the Swami, and with my superfluity of reverence found not a word to say.

Of the lecture that evening I can recall nothing. The imposing figure on the platform in red robe, orange cord, and yellow turban, I do remember, and the wonderful mastery of the English language with its rich sonorous tones, but the ideas did not take root in my mind, or else the many years since then have obliterated them. But what I do remember was the symposium that followed.

To our house came the College president, the head of the philosophy department, and several other professors, the ministers of the Northampton churches, and a well-known author. In a corner of the living-room we girls sat as quiet as mice and listened eagerly to the discussion which followed. To give a detailed account of this conversation is beyond me, though I have a strong impression that it dealt mainly with Christianity and why it is the only true religion. Not that the subject was the Swami’s choosing. As his imposing presence faced the row of black-coated and somewhat austere gentlemen, one felt that he was being challenged. Surely these leaders of thought in our world had an unfair advantage. They knew their Bibles thoroughly and the European systems of philosophy, as well as the poets and commentators. How could one expect a Hindu from far-off India to hold his own with these, master though he might be of his own learning? The reaction to the surprising result that followed is my purely subjective one, but I cannot exaggerate its intensity.

To texts from the Bible, the Swami replied by other and more apposite ones from the same book. In upholding his side of the argument he quoted English philosophers and writers on religious subjects. Even the poets he seemed to know thoroughly, quoting Wordsworth and Thomas Gray (not from the well-known Elegy). Why were my sympathies not with those of my own world? Why did I exult in the air of freedom that blew through the room as the Swami broadened the scope of religion till it embraced all mankind? Was it that his words found an echo in my own longings, or was it merely the magic of his personality? I cannot tell, I only know that I felt triumphant with him.

Early the next morning loud splashings came from the bathroom, and mingling with them a deep voice chanting in an unknown tongue. I believe that a group of us huddled near the door to listen. At breakfast we asked him the meaning of the chant. He replied. “I first put the water on my forehead, then on my breast, and each time I chant a prayer for blessings on all creatures”. This struck me forcibly. I was used to a morning prayer, but it was for myself first that I prayed, then for my family. It had never occurred to me to include all mankind in my family and to put them before myself.

After breakfast the Swami suggested a walk, and we four students, two on each side, escorted the majestic figure proudly through the streets. As we went, we shyly tried to open conversation. He was instantly responsive and smiled showing his beautiful teeth. I only remember one thing he said. Speaking of Christian doctrines, he remarked how abhorrent to him was the constant use of the term “the blood of Christ”. That made me think. I had always hated the hymn “There is a fountain filled with blood, drawn from Emmanuel’s veins”, but what daring to criticize an accepted doctrine of the Church! My “free-thinking” certainly dates from the awakening given me by that freedom-loving soul. I led the conversation to the Vedas, those holy books of India he had mentioned in his lecture. He advised me to read them for myself, preferably in the original. I then and there made a resolve to learn Sanskrit, a purpose which I regret to say I have never fulfilled.“

But Martha never forgot the brief encounter, so much so that over four decades later, she made a trip east, eventually arriving in Belur to pay her respects to the memory of the monk who stayed at Smith for a few days in the spring of her freshman year. I went to America to discover new ideas, and three decades later, found the old ones pulsing anew. Martha’s path was destined to cross Swamiji’s when she was eighteen, and he made an impact on her that lasted all her life. Mine was destined to come across Swamiji’s story from birth, but the personal impression came far later. The penny finally dropped. In my case, all those childhood visits of little remembrance seemed to bear wonderful fruit decades later. In its own place and time, each life seemed to grow toward greater insight about its seemingly chance events.

Nothing is wasted or random. We may think we travel far from or toward God, but divinity breathes within us, shaping the patterns of our lives—new experiences are not any farther from the source than the old were. If you didn’t value what was once in your reach, the passage of time and crucible of life can bring its significance home. In Martha’s words:

“I often think of the time I have lost, of the roundabout way I have come, groping my way, when under such guidance I might have aimed directly for the goal. But for an immortal soul it is wiser not to spend time in regrets, since to be on the way is the important thing.

One reads of the seeds found in Egyptian sarcophagi, buried thousands of years previously and yet retaining enough vitality to sprout when planted. Lying apparently lifeless in my mind and heart, the far-off memory of that great apostle from India has during the past year begun to send forth shoots. It has at last brought me to this country. During the intervening years — years of sorrow and responsibility and struggle mingled with joy — my inmost self has been trying out this and that doctrine to see if it was what I wanted to live by. Always some dissatisfaction resulted. Dogmas and rituals, made so important by orthodox believers, seemed to me so unimportant, so curbing that freedom of the spirit that I longed for.

I find in the universal Gospel that Swamiji preached the satisfaction of my longing. To believe that the Divine is within us, that we are from the very first a part of God, and that this is true of every man. what more can one ask? In receiving this, as I have on the soil of India, I feel that I have come Home.”

And, like Martha, I find I come home—everywhere I go. There is no distance to travel from our essence, as we are reminded again and again.

Usha Kutty Juman is a publishing professional, writer and artist, who has lived in Kolkata, India and the US. She has studied philosophy formally, but in her practical spiritual development she was taught directly by Triprayar Shiva Yogini Amma and Amritanandamayi Devi. She can be contacted at ujuman@gmail.com.

Resources:

1. http://vivekanandaabroad.blogspot.com/2015/12/northampton-ma-15-april-1894.html?view=sidebar

2. http://www.vivekananda.net/PDFBooks/Reminiscences/Fincke.html