Edited and Introduced by Katherine Bucknell

Foreword by Christopher Hitchens

756 pages. Harper/HarperCollins.

$39.99.

Review by Karl Whitmarsh

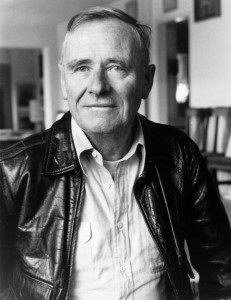

A Singular Man

On November 30th, 1962, Christopher Isherwood spent several turbulent hours at the bedside of actor Charles Laughton, his friend and neighbor, who was dying slowly of cancer. Laughton himself was uncharacteristically at peace; it was Isherwood who fought noisily with his own mind, tormented by his own egotistical ramblings, unsure of how to pray or to whom. Returning home, Isherwood wrote in his diary:

“The really important question is, why should one pray to Ramakrishna for Charles? Does it do any good? Granted that Ramakrishna is ‘there,’ available, only waiting to be asked, shouldn’t one simply tell Charles to ask him, or ask Christ, or whatever avatar he believes in? I must ask Swami [Prabhavananda] about this when I see him next.”1

The following week, with these questions weighing heavily on his mind, Isherwood went to see his spiritual teacher, who reassured him with words of calm simplicity:

“Swami, when asked about prayer, said that it is good both for you and for the person you pray for; and he added, ‘you see, when you are speaking to God like that, there are not two people, it’s all the same.’ He also said that all that was needed was faith that the prayer would be answered. You didn’t have to be a saint . . . He said that with that absolute compelling confidence of his. He made you feel he was quite quite sure of what he was saying.”2

The second volume of Isherwood’s diaries – The Sixties – is strewn with many spiritual gems like this. Yet the real brilliance of his life is visible only when one resets the gems in their original, cloudy setting – the hedonistic, Hollywood-centered circle of Isherwood’s friends and colleagues.

His conscience was burdened with endless regrets about wasted time and especially about evenings squandered in drink and drunkenness.

His was, as he would have been the first to admit, a grinding existence of continuous frustration and frenetic tawdriness. His conscience was burdened with “endless regrets about wasted time and especially about evenings squandered in drink and drunkenness,” as Christopher Hitchens notes in the foreword. But the details – sometimes colorful, sometimes homely – of Isherwood’s daily life draw a more authentic picture of his spiritual strivings than holy anecdotes alone. The diaries narrate eloquently how one seeker, through singular effort, succeeded in spiritualizing himself and his view of the world.

Vedantists who knew Isherwood and the people about whom he wrote will find these diaries to be a particularly savory dish of holy gossip. Of course the unfortunate recipients of his barbed wit may feel otherwise. (I did know him slightly but am not mentioned here.) Still others will find the diaries appealing for their celebrity content: descriptions of beach-walks and dinner gatherings with prominent actors, directors and producers of the day.

The content of the diaries is often mundane – partly because the author’s main intent was to jot down his unvarnished recollections as raw material for future writings, and partly because celebrity glamour left Isherwood genuinely unimpressed. To him, these were merely co-workers laboring alongside him in the studio mill, or self-important executives talking big but equally enslaved by the Hollywood machine – ordinary people, full of fear and insecurity like anyone else.

Isherwood, made famous by his Berlin novels, left his native England in 1939 to settle in Southern California.

Christopher Isherwood, made famous by his Berlin novels in the 1930s, left his native England in 1939 to settle permanently in Southern California. Earlier he had met Gerald Heard and Aldous Huxley, who would soon introduce him to Swami Prabhavananda. The swami was quick to make use of his new disciple’s talents, enlisting his assistance in the swami’s translation of the Bhagavad Gita. Isherwood went on to translate many more books with Swami Prabhavananda, including How to Know God, the Crest Jewel of Discrimination, Narada Bhakti Sutras and Srimad Bhagavatam: The Wisdom of God, and popular Vedanta prayers such as Chant the Name of the Lord and Breaker of This World’s Chain. Vedanta books penned by Isherwood on his own include Ramakrishna and his Disciples and The Wishing Tree (a collection that includes An Approach to Vedanta).

In 1943 Isherwood went to live at the Vedanta Society to help Swami Prabhavananda with his translation of the Gita.

In 1943 Isherwood went to live at the Vedanta Society in Hollywood to help Swami Prabhavananda with his translation of the Gita.

He remained there for over two years. It is unlikely that Isherwood was ever seriously inclined to become a monk; but for the rest of their lives together, Swami would tease him about the possibility. Before their trip to India together in 1963, Swami remarked affectionately to his disciple “you could have been a swami but perhaps you are more useful to us this way”.

But Isherwood was irrevocably committed to his literary vocation, which implied to him the conscious witnessing of and involvement in secular life: life in the “real” world and in the world of literary fiction, of Hollywood make-believe. This latter world – the world of movies – had fascinated him since he was a boy. He drew his livelihood and artistic sustenance from illusions – how could he pretend or even desire to disengage himself from them completely?

His way of escape from the world’s degradation was to describe it with intensity, dispassion and frankness. A yoga of writing, in other words. As his guru had often stated, art, music, and writing were all potential avenues to divine realization. “When I work, I declare a state of emergency,”3 he wrote, aware that the perfected karma yogi acts always with focus and intent. In a similar vein he heeded the advice given him by E.M. Forster: “Get on with your own work: behave as if you were immortal.”

While the style of the diaries is casual, the writing is precise — he conjures vivid and memorable characters.

Though the style of the diaries is casual, the writing is precise. As in his fiction, he conjures vivid and memorable characters with a few lean, impressionistic strokes. Luckily for a novelist, he had a natural interest in people – he spent most of his evenings socializing, often in large parties. But far from interfering with his writing, the busy social life nurtured it.

Nevertheless, Isherwood gradually realized that writing was ultimately of no use to him except as a vehicle to make sense of the world. And to make sense of the world, he would need a philosophy. Of his evolving attitude during the 1930s Isherwood wrote, “I no longer believed in Art as an absolute aim and justification of a human life. Certainly I still intended to write books; but writing, in itself, wasn’t enough for me. It might occupy most of my time, but it couldn’t be my means of spiritual support, my religion.”4

This attitude understandably puzzled his fellow writers. Somerset Maugham, he recalled, “had believed I’d be one of the most successful novelists of my generation—‘and then,’ said Maugham, ‘you threw it all away [for personal happiness and religion].’ ”5

If others thought him lacking in ambition, Isherwood did not disagree. “[My vice] is vanity [not ambition] . . . I bother very little about whether or not I have succeeded; maybe because I feel that I have, according to my rules. What I am concerned about is whether or not other people recognize the fact of my success. And this concern arises from vanity, not ambition.”6

Though Isherwood professed to be vain, the opinions of his peers came to matter to him less and less.

But in fact, though Isherwood professed to be vain, the opinions of his peers came to matter to him less and less. The philosophy of Vedanta, with its emphasis on divine realization, increasingly informed his writing and his world-view. And the man who to Isherwood embodied this philosophy – his spiritual teacher – was a still more important influence than the philosophy itself. “I don’t go to Swami for ethics, but for spiritual reassurance,” he wrote on Nov. 22, 1962. ‘Does God really exist? Can you promise me he does?’ Not, ‘Ought I, ought I not to act in the following way?’ I feel this so strongly that I can quite imagine doing something of which I know Swami disapproves – but which I believe to be right, for me – and then going and telling him about it . . . . Advice on how to act – my goodness, if you want that, you can get it from a best friend, a doctor, a bank manager.”7

There were many times he did in fact behave in ways he knew Swami Prabhavananda would not approve. As a result, Isherwood took pains to avoid appearing as a representative of Vedanta, and especially would refuse to give lectures. At Swami’s request, he put these scruples aside when they traveled together to India for the Vivekananda centenary in December 1963. But he quickly regretted agreeing to the India trip and its attendant duties, and his resentment festered steadily until it erupted in an abrupt (though less than spontaneous) tantrum two weeks into their Indian stay:

Isherwood to Swami: “I can’t ever talk about God and religion in public again. It’s impossible. I’ve felt like this for a long time . . . it’s the same thing, really, that I told you years ago when I was living at the [Vedanta] center: the Ramakrishna Math is coming between me and God. I can’t belong to any kind of institution. Because I’m not respectable – ”

Swami: “But Chris, how can you say such things? You’re almost too good. You are so frank, so good . . .”

“I can’t stand up on Sundays in nice clothes and talk about God. I feel like a prostitute.”

Isherwood: “I can’t stand up on Sundays in nice clothes and talk about God. I feel like a prostitute . . . I should never have agreed to come to India . . . ”

Swami: “O Chris, I’m sorry, I shouldn’t have asked you [to come] . . . Nobody here expects (pranams) of you . . . I don’t want to lose you.” . . . He looked at me with hurt brown eyes.8

That his guru loved him unconditionally was a difficult notion for Isherwood to accept. Consequently, he came to understand that accepting his guru’s love was actually a major part of his own spiritual practice. “Swami loves me – I don’t care why and I can’t possibly ever get to know why – but I ought to be able to feel that I’m under the protection of his love. Isn’t that more than enough?”9 he wrote on July 18, 1966.

“What do I feel? Stupid, dull, unfeeling, fat, old… A stupid old toad – and not even ashamed of being one.”

When it came to his own devotion and spiritual progress, Isherwood was relentlessly self-deprecating. “My religion consists in making japam without the slightest devotion.”10 He often referred to himself as old Dobbin, the plodding, colorless draft horse. In a moment of particularly rampant self-pity he wrote: “What do I feel? Stupid, dull, unfeeling, fat, old. Utterly unfit to associate with Prabhavananda, or with Don [his longtime lover and companion] either. A stupid old toad – and not even ashamed of being one. Too dull for shame.”11

One would not know this, however, from seeing Isherwood in the presence of Swami Prabhavananda. Sitting alone with the swami, or in a small group, he seemed spellbound like a little boy in front of a favorite uncle. On the other hand, placed among the Vedanta Sunday crowd he seemed aloof, but one could ascribe that to shyness or British upper-class reserve. However, most Vedantists saw him only at the annual Father’s Day event and at the Wednesday evening readings in Hollywood – and knew less about him than they supposed.

On June 18, 1966, he attended a festive Father’s Day event at the Vedanta Society, replete with amateur musical and dance numbers written especially for the occasion. The songs, which were mostly in honor of his guru, were unabashedly corny and sentimental. “Only the very stupid or pure in heart can listen to this kind of thing without squirming,” he noted.

Some of the songs though were about Isherwood:

Now he’s a chappie

mild and mannered

With a proper savoir-faire

With bushy-browed expressions

He will soon your heart ensnare . . .

“‘Now you know how much we all love you!’ she cooed… perhaps I am… liked, as an institution rather than a person.”

“I squirmed, but I was touched of course and pleased. It is a family, even though I know so few of my relatives and can’t honestly take much interest in them. Some woman came up to me afterwards and well-meaningly cooed, ‘Now you know how much we all love you!’ Well, perhaps I am mildly liked – as an institution rather than a person – and that’s quite sufficient.

“I have always been and am now more than ever alien from the society as such. Only Swami’s loyalty has forced them to accept me – for of course there must be all manner of lurid (and fairly accurate) rumors about my life. And then there are those dreadful novels of mine for the faithful to gag on. The fact that I’ve written a life of Ramakrishna and translated the Gita must only make my novels the less excusable in their eyes. It really is a very strange and comic situation – but I’m so accustomed to it that I seldom think about it.”12

“I don’t know what Swami sees in him,” my aunt Prasanna said to me one day.

Despite his protestations to the contrary, he did in fact think about it, as did others. “I don’t know what Swami sees in him,” my aunt Prasanna said to me one day, after I told her about an Isherwood novel I had recently been reading. Then she went on to describe his allegedly salacious writing, which I am quite sure she knew of only second-hand. But softened perhaps by my favorable opinion, when Isherwood came to speak at the Santa Barbara temple a week or two later, she shook his hand cordially after the talk and expressed her appreciation for it.

Her perplexity was typical. Except for the most naïve or the most detached, it required considerable effort for the local Vedantists to reconcile the spiritual and worldly sides of the famous novelist ill at ease in their midst.

Some of them perhaps appreciated that the effort was no more easy – and much more painful – for Isherwood himself. The man who referred to himself as an “institution” was at once proud and resigned, vulnerable and aloof, and revolted by the thought of being judged.

Making much of his own vices, he was slow to acknowledge his own virtues. As Hitchens notes in his foreword, “Beneath all this hedonism and experiment there still remains a somewhat austere and self-reproaching English public-school man of the kind he’d sworn to escape, forever piously reproving his own backslidings, vowing to do more manly exercises.” In this regard Isherwood was fortunate to have met a teacher who was also a friend, one who could objectively gauge his disciple’s virtues and failings – a teacher who was convinced that Isherwood was, if nothing else, sincere.

Truthfulness was the essential virtue for householders in general, and the surest path for Isherwood in particular.

The force of the swami’s belief left its imprint on his disciple, who over time became convinced that sincerity and truthfulness mattered above all else. Truthfulness was the most essential virtue for householders in general, and the surest path for Isherwood in particular. Meditating on its ramifications, the disciple put to paper an unusual appreciation of Ramakrishna:

The greatness of Ramakrishna is not expressed by the fact that he was under all circumstances “pure’.

“. . . Swami [Prabhavananda] used to teach me that purity is telling the truth . . . The greatness of Ramakrishna is not expressed by the fact that he was under all circumstances “pure’. No. And even if he was pure, that didn’t mean that he wasn’t capable of anything. You always feel that about him – there was nothing that he might not have done – except one thing – tell a lie. So, when I hear this story about him and [his presumed lust for] Naren, I do not say to myself, “He was incapable of it.” I say to myself, “I know it isn’t true, because if he had felt any lust for Naren, he would have been incapable of not telling everyone about it.’ This seems to me basically important . . . It’s funny that I, who am steeped in sex up to the eyebrows, can see quite clearly what Ramakrishna’s’ kind of purity is capable of, and that most people just can’t . . . I am privileged, far more than I realize most of the time.”13

A not inconsequential corollary to Isherwood’s quest for sincerity was his light-hearted attitude toward the pomp and formalities of his adopted religion. Though he had sincere respect for Indian swamis, he recognized that they were nonetheless human. He found their pretensions a great source of amusement – as he was certain no less a holy man than Vivekananda himself would have done. Isherwood, whose own work was marked by irony and droll humor, was greatly impressed by Vivekananda’s wit and disdain for any kind of humbug. “He appealed to me as the perfect anti-Puritan hero: the enemy of Sunday religion, the destroyer of Sunday gloom, the shocker of prudes . . . the comedian who taught the deepest truths in idiotic jokes and frightful puns. That humor had its place in religion, that it could actually be a mode of spiritual self-expression, was a revelation to me.”14

“I loathed [the] gravity [of Christians],” he wrote, “their humility, their lack of humor…”

His early religious upbringing had left a permanent mark on Isherwood. “I loathed [the] gravity [of Christians],” he wrote, “their humility, their lack of humor, their special tone when speaking of their God.”15 He was not about to show blind reverence to the acolytes of his new religion any more than he had to the followers of the old one.

So we should not find it surprising that even before his arrival in India in December 1963, Isherwood humorously but discreetly vented his resentment in the pages of his diary. He had not wanted to make the upcoming trip. He had agreed to travel with Swami out of a mistaken sense of propriety. He wrote partly out of frustration and partly to amuse himself:

“The parting was like a funeral which is so boring and hammy and dragged out that you are glad to be one of the corpses.”

“It is no annihilating condemnation of the devotees – about fifty of whom had come to the airport to see us off – to say that they would have felt somehow fulfilled if our plane had burst into flames on take-off, before their eyes. They had built up such an emotional pressure that no other kind of [release] could have quite relieved it. The parting was like a funeral which is so boring and hammy and dragged out that you are glad to be one of the corpses. Anything rather than have to go home with the other mourners afterwards!”16

As he had predicted, he spent most of the next three weeks in India feeling lonely, bored and sorry for himself. His journal brought him some relief, as in its pages he quietly flayed the more annoying of his hosts and the customs that he could not comprehend and did not even pretend to want to understand.

Yet as the years pass, there are fewer traces in the diary of petulance, self-pity, and self-doubt. The author’s voice grows calmer, more assured and more accepting.

He did not come easily to this transformation. It came only after he had attained some stability in his turbulent relationship with Don. In the early years of the diary he made weary note of the intermittent quarrels and misunderstandings between Don and himself, due at least partly to their difference in age. Thirty years his junior, Don was obsessed with discovering his own talent and gaining recognition for it, whereas the older man had long since stopped caring about such things. As Isherwood noted, “Don has to come to terms with success-failure. I have to come to terms with death.”17

“I really do not find my own company amusing… I wish God were nearer, and yet, in a dull way, I know he’s there.”

Whatever their differences, as Isherwood grew older, Don was more and more his solace. “I long for Don to come back – so I can love and think and feel and be a human being again. At present I’m just a dull old dying creature. I really do not find my own company amusing, and yet I often prefer to be alone. I wish God were nearer, and yet, in a dull way, I know he’s there.”18

“One of my daily meditations ought to be on just exactly what it means or should mean, to me at my age, to have Don in my life. It is nothing less than a blazing miracle.”19

He came to the conviction that human love and divine love were not really different. There was only one love, love alone mattered, and he could realize that love in his own life. “I woke this morning thinking that the real point of a householder’s life is not simply that he is not a monk but that he loves a human being rather than God. So he must learn to love God through that human being. Very obvious and very important to remember.”20

Religion is the practice of oneness with the infinite, the principle that dwells in the hearts of all beings, through the feeling of love. (Swamiji)

“I realize more than ever that this is IT. Not just an individual, or just a relationship, but THE WAY. The way through to everything else. This seemed to be obliquely confirmed by Swami this morning. He is after me to find a title for a volume of Vivekananda’s letters in English, and he called me because he thought he had found a clue to it in a quotation from one of the letters. Vivekananda writes, ‘Religion is the practice of oneness with the infinite, the principle that dwells in the hearts of all beings, through the feeling of love.’

“There may be interruptions from the static of egotism and possessiveness, but at least you are on the right wavelength.”

If you are tuned in on personal love, then you are on the same wavelength as infinite love. There may be terrific interruptions from the static of egotism and possessiveness, but at least you are on the right wavelength and that’s a tremendous achievement in itself.”21

The editor is to be thanked for her thorough glossary, and her thoughtful efforts to conceal identities and suppress passages that might discomfit those acquaintances of Isherwood who still survive. Don Bachardy, who courageously made these very private diaries available to the public, also deserves our deep appreciation.

Footnotes

1 Diaries, pg. 247

2 pg. 248

3 pg. 291, Dec. 31, 1963

4 The Wishing Tree, Vedanta Press, 1987, pg. 8

5 Diaries, pg. 112, Sept. 15, 1961

6 idem, pg. 349, Nov. 23, 1965

7 pg. 243

8 pg. 325, Jan. 2, 1964

9 pg. 401- 402

10 pg 291, October 31, 1963

11 pg. 357, March 15, 1965

12 pg. 398

13 pg. 231, Oct. 16, 1962

14 The Wishing Tree, pg. 59

15 idem, pg. 10

16 Diaries, pg. 301, Dec. 18, 1963

17 pg. 371, July 24, 1965

18 pg. 510, Apr. 24, 1968

19 pg. 355, Feb. 24, 1965

20 idem, pg. 486

21 pg. 510 – 511, Apr. 26, 1968

KARL WHITMARSH has been associated with the Vedanta Society of

Southern California (VSSC) since 1970. He was recently elected President of VSSC’s Board of Directors.